HIV Prevention and Care for Older Adults

OVERVIEW

The Association of Nurses in AIDS Care (ANAC, 2023) is a national and global association that “fosters the professional development of nurses and others involved in the delivery of healthcare for persons at risk for, living with, and/or affected by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and its co-morbidities. The Association of Nurses in AIDS Care promotes the health, welfare and rights of people living with HIV around the world.” As such, this association collaborates with clinicians and researchers to create and support care standards and guidelines for PLWH that include many who are aging. Aging with HIV is quite common, thanks primarily to improved ART and improved care coordination. The following five topics represent clinical updates and guidance that are highly relevant to those living with HIV and aging and their clinicians. They represent advancing clinical protocols for now and in the future: (a) creating Age-Friendly Health Systems, (b) using a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA), (c) understanding experiences of everyday ageism and the health of older U.S. adults, (d) using holistic care, and (e) using the 4Ms.

The Association of Nurses in AIDS Care (ANAC, 2023) is a national and global association that “fosters the professional development of nurses and others involved in the delivery of healthcare for persons at risk for, living with, and/or affected by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and its co-morbidities. The Association of Nurses in AIDS Care promotes the health, welfare and rights of people living with HIV around the world.” As such, this association collaborates with clinicians and researchers to create and support care standards and guidelines for PLWH that include many who are aging. Aging with HIV is quite common, thanks primarily to improved ART and improved care coordination. The following five topics represent clinical updates and guidance that are highly relevant to those living with HIV and aging and their clinicians. They represent advancing clinical protocols for now and in the future: (a) creating Age-Friendly Health Systems, (b) using a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA), (c) understanding experiences of everyday ageism and the health of older U.S. adults, (d) using holistic care, and (e) using the 4Ms.

CREATING AN AGE-FRIENDLY HEALTH SYSTEM

This is an initiative of The John A. Hartford Foundation and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), in partnership with the American Hospital Association (AHA) and the Catholic Health Association of the United States (CHA; www.ihi.org/initiatives/age-friendly-health-systems).

A. Summary

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the U.S. population age 65+ years is expected to nearly double over the next 30 years, from 43.1 million in 2012 to an estimated 83.7 million in 2050. These demographic advances, however extraordinary, have left our health systems behind as they struggle to reliably provide evidence-based practice to every older adult at every care interaction. The Age-Friendly Health Systems is an initiative of The John A. Hartford Foundation and the IHI, in partnership with the AHA and the CHA, designed to meet this challenge head on. The Age-Friendly Health Systems aims to:

- Follow an essential set of evidence-based practices

- Cause no harm

- Align with what matters to the older adult and their family caregivers

B. What does it mean to be age-friendly for those aging with HIV?

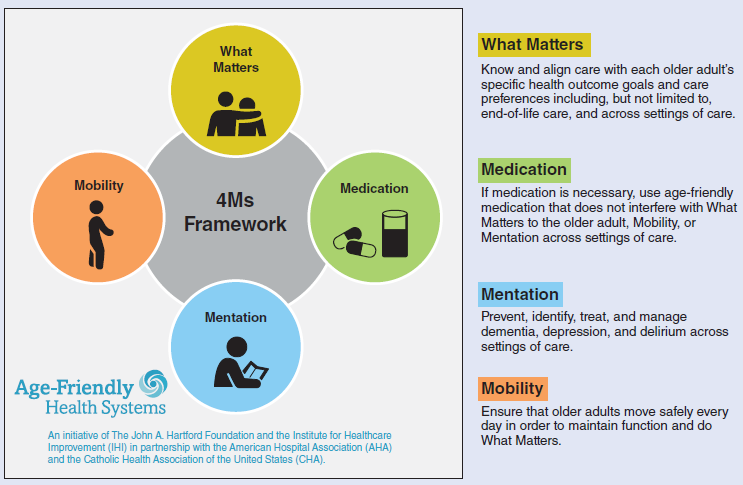

Becoming an Age-Friendly Health System entails reliably providing a set of four evidence-based elements of high-quality care, known as the “4Ms,” to all older adults in your system: What Matters, Medication, Mentation, and Mobility (see Figure 17.3 and Section V for implementation of 4Ms).

Figure 17.3 Implementation of 4Ms.

Source: From Age-Friendly Health Systems (an initiative of The John A. Hartford Foundation and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, in partnership with the American Hospital Association and the Catholic Health Association of the United States). (2020). Age-friendly health systems. https://www.ihi.org/initiatives/age-friendly-health-systems.

USING A CGA

A. Summary

People with HIV are living longer lives and experiencing accentuated aging. CGA has been proposed to identify and help meet each individual patient’s needs. Researchers performed a retrospective review of the results of CGA in an HIV clinic in New York City. CGA included assessment of basic and instrumental activities of daily living, and screening for depression, anxiety, frailty, cognition, and quality of life, along with general discussion of concerns and goals. They compared the group of people living with HIV referred for CGA with those of comparable age who were not referred to determine the factors that were associated with referral. They conducted a descriptive analysis of those undergoing CGA, along with a statistical regression to determine factors associated with poorer Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2; mental health) depression scores and higher Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS) scores. A total of 105 patients underwent full CGA during the study period. The mean age of referred patients was 66.5 years, ranging from 50 to 84 years (SD = 7.99). More than 92% were virally suppressed. Compared with their nonreferred counterparts over 50, referred patients were older and had more functional comorbidities, like cerebrovascular disease, neuropathy, and urinary incontinence. More than half complained of fatigue, and two-thirds noted poor memory. Almost 60% were frail or prefrail. Ninety patients were asked about their goals, and the most cited were related to health or finances; 15 patients were unable to articulate any goals. Having fewer goals and noting weight loss or fatigue were predictive of higher scores on the PHQ-2 depression screen. The key takeaway for clinicians is that older persons with HIV (PWHs) undergoing CGA can manage their activities of daily living, and many have concerns and deficits beyond their comorbidities. CGA offers an important window into the psychosocial concerns and needs of older PWHs.

UNDERSTANDING EXPERIENCES OF EVERYDAY AGEISM AND THE HEALTH OF OLDER U.S. ADULTS

A. Summary

Major incidents of ageism have been shown to be associated with poorer health and well-being among older adults. Less is known about routine types of age-based discrimination, prejudice, and stereotyping that older adults encounter in their day-to-day lives, known as everyday ageism. Researchers examined the prevalence of everyday ageism, group differences and disparities, and associations of everyday ageism with indicators of poor physical and mental health. They used a cross-sectional survey data from the December 2019 National Poll on Healthy Aging among a nationally representative household sample of U.S. adults 50 to 80 years of age. Data were analyzed from November 2021 through April 2022. Experiences of everyday ageism were measured using the newly developed multidimensional Everyday Ageism Scale. Key findings in this population include (a) fair or poor physical health, (b) a number of chronic health conditions, (c) fair or poor mental health, and (d) prominence of depressive symptoms.

USING HOLISTIC CARE

A practical toolkit for providing holistic care for aging people with HIV includes information about comorbidities and polypharmacy, screening and managing chronic diseases, coordinating care across different specialists, and mental health wellness.

A. Summary

PRIME Education, supported by a grant from Gilead Sciences, Inc., provides for clinicians four key components of care directed to those who are aging and living with HIV. These components include emphasis on individualized treatment decision-making; coordination of comprehensive care, especially with those with comorbidities and coinfection; assessment; and support of mental, emotional, and social wellness, and taking ownership of health and self-care.

USING THE 4Ms

From the IHI, read about how to use the 4Ms (What Matters, Medication, Mentation, Mobility) in caring for older adults.

A. Summary

In 2020, the IHI produced a guide to using the 4M model (see Section I of this protocol and Chapter 45, “Age-Friendly Health Systems,” for more information). This guidebook includes the history of the model’s inception and development, as well as how to put the model into practice using a Plan-Do-Study-Act approach to quality improvement. The following are the four areas of focus in the model:

- What Matters: Know and align care with each older adult’s specific health outcome, goals, and care preferences, including but not limited to end-of-life-care and across settings of care.

- Medication: If medication is necessary, use age-friendly medication that does not interfere with what matters to the older adult, mobility, or mentation across settings of care.

- Mentation: Prevent, identify, treat, and manage, dementia, depression, and delirium across settings of care.

- Mobility: Ensure that older adults move safely every day to maintain function and do what matters.

----

Updated: January 2025

Boltz PhD, RN, GNP-BC, FGSA, FAAN, M., Capezuti, PhD, RN, FAAN, E.A., & Fulmer PhD, RN, FAAN, T. T. (2025). Evidence-Based Geriatric Nursing Protocols for Best Practice (7th ed.). Springer Publishing. Retrieved December 17, 2024, from https://www.springerpub.com/evidence-based-geriatric-nursing-protocols-for-best-practice-9780826152763.html#tableofcontents

Chapter 17, DeMarco, R.F. & Alberts, L.H. (2025) HIV Prevention and Care in the Older Adult

REFERENCES

Brown, T. T., & Guaraldi, G. (2017). Multimorbidity and burden of disease. In M. Brennan-Ing & R. F. DeMarco (Eds.), HIV and aging (pp. 59–73). Basel, Switzerland: Karger. Evidence Level V.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1999). AIDS among persons aged>50 years: United States, 1991–1996. Atlanta, GA: Author. Evidence Level I.

Chiao, E., Ries, K., & Sande, M., (1999). AIDS and the elderly. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 28, 740–745. doi:10.1086/515219. Evidence Level V.

Costagliola, D. (2014). Demographics of HIV and aging. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS, 9, 294–301. doi:10.1097/COH.0000000000000076. Evidence Level I.

Eden, K. J., & Kevan, R. W. (2009). Quality of sexual life and menopause. Women’s Health, 5(4), 385–396. doi:10.2217/whe.09.24. Evidence Level IV.

Furlotte, C., & Schwartz, K. (2017). Mental health experiences of older adults living with HIV: Uncertainty, stigma, and approaches to resilience. Canadian Journal on Aging, 36(2), 125–140. doi:10.1017/S0714980817000022. Evidence Level IV.

Gleason, L. J., Luque, A. E., & Shah, K. (2013). Polypharmacy in the HIV infected older adult population. Clinical Interventions and Aging, 8, 749–763. doi:10.2147/CIA.S37738. Evidence Level IV.

Greene, M., Covinsky, K. E., Valcour, V., Miao, Y., Madamba, J. Lampiris, H., … Deeks, S. G. (2015). Geriatric syndromes in older HIV-infected adults. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 69, 161–167. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000000556. Evidence Level V.

Harkness, G. A., & DeMarco, R. (2016). Community and public health nursing: Evidence for practice. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. Evidence Level V.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS. (2014). The gap report. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS. Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_Gap_report. Evidence Level V.

Kovacs, P. J., Bellin, M. H., & Fauri, D. P. (2006). Family-centered care: A resource for social work in end-of-life and palliative care. Journal of Social Work in End of Life Palliative Care, 2, 13–27. doi:10.1300/J457v02n01_03. Evidence Level V.

Krall, E., Close, J., Parker, J., Sudak, M., Lampert, S., & Colonnelli, K. (2012). Innovation pilot study: Acute care for elderly (ACE) unit-promoting patient-centric care. Health Environments Research and Design Journal, 5(3), 90–98. doi:10.1007/s10592-007-9394-z. Evidence Level IV.

McDonald, K., Elliott, J., & Saugeres, L. (2013). Aging with HIV in Victoria: Findings from a qualitative study. HIV Australia, 11, 13. Retrieved from https://www.afao.org.au/article/ageing-hiv-victoria-findings-qualitative-study/. Evidence Level IV.

McVey, J., Madill, A., & Fielding, D. (2001). The relevance of lowered personal control for patients who have stoma surgery to treat cancer. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 40(4), 337–360. doi:10.1348/014466501163841

Negin, J., Nemser, B., Cumming, R., Lelerai, E., Amor, Y. Ben, & Pronyk, P. (2012). HIV attitudes, awareness and testing among older adults in Africa. AIDS and Behavior, 16(1), 63–68. doi:10.1007/s10461-011-9994-y. Evidence Level IV.

Shorthill, J., & DeMarco, R. F. (2017). The relevance of palliative care in HIV and aging. In M. Brennan-Ing & R. F. DeMarco (Eds.), HIV and aging (pp. 159–172). Basel, Switzerland: Karger. Evidence Level V.

Sprague, C., & Brown, S. M. (2017). Local and global HIV aging demographics and research. In M. Brennan-Ing & R. F. DeMarco (Eds.), HIV and aging (pp. 159–172). Basel, Switzerland: Karger. Evidence Level V.

World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. (2013). Regional health sector strategy on HIV, 2011–2015. -Geneva, Switzerland: Author. Evidence Level V.

Donation

Donation