Prior to the distribution of the COVID-19 vaccines, adults 65+ accounted for 14% of the COVID-19 infections in the U.S., yet they comprised 80% of the COVID-19 deaths. There was no question, therefore, that older adults would need to be prioritized to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. However, little attention was given as to how this group would actually access the vaccine or to the fact that societal structures have historically hampered this vulnerable population from equitable access to needed resources and services.

Structural inequity refers to the systematic disadvantage of one social group compared to other groups with whom they coexist, and it is deeply embedded in the fabric of society in which resources and opportunities are differentially allocated. The most commonly disadvantaged groups affected by structural inequities are older adults, racial/ethnic minorities, low-income groups, socially isolated and homebound individuals, and those who live in rural settings.

In the case of older adults’ access to the COVID-19 vaccine, this inequity especially occurs in relation to barriers around internet use, transportation, and digital literacy. For example, although the internet was the primary source for scheduling vaccine appointments early on in the pandemic, in 2018, more than 1 in every 4 Medicare beneficiaries did not have access to the internet. Those without internet access were more likely to be 85 years or older, members of racial or ethnic minority communities, and those from low-income households. The average monthly cost of internet access is about $70, which can be out of reach for people with limited incomes. And for the almost 13.8 million older adults in the U.S. who live alone, asking for help with tasks such as registering online for a vaccine or getting to the appointment may not have been an option. In addition, between 2 million and 4.4 million older adults are homebound. Most are in their 80s and have multiple medical conditions, such as heart failure, cancer, and chronic lung disease, and many are also functionally limited and cognitively impaired, making it difficult for them to travel to appointments and wait in long lines to get the vaccine.

Vaccine access, however, is just a microcosm of the structural inequities experienced by older adults and particularly those with fewer resources. These inequities exist in access to healthcare (e.g., lack of accessible pharmacies, hospitals, and providers), in availability of healthy foods (e.g., more likely to see a bodega in low-income communities than a Whole Foods store), in opportunities for socialization (e.g., walkable neighborhoods that are clean and safe), in a lack of affordable housing, and in a lack of access to community resources (e.g., parks, schools).

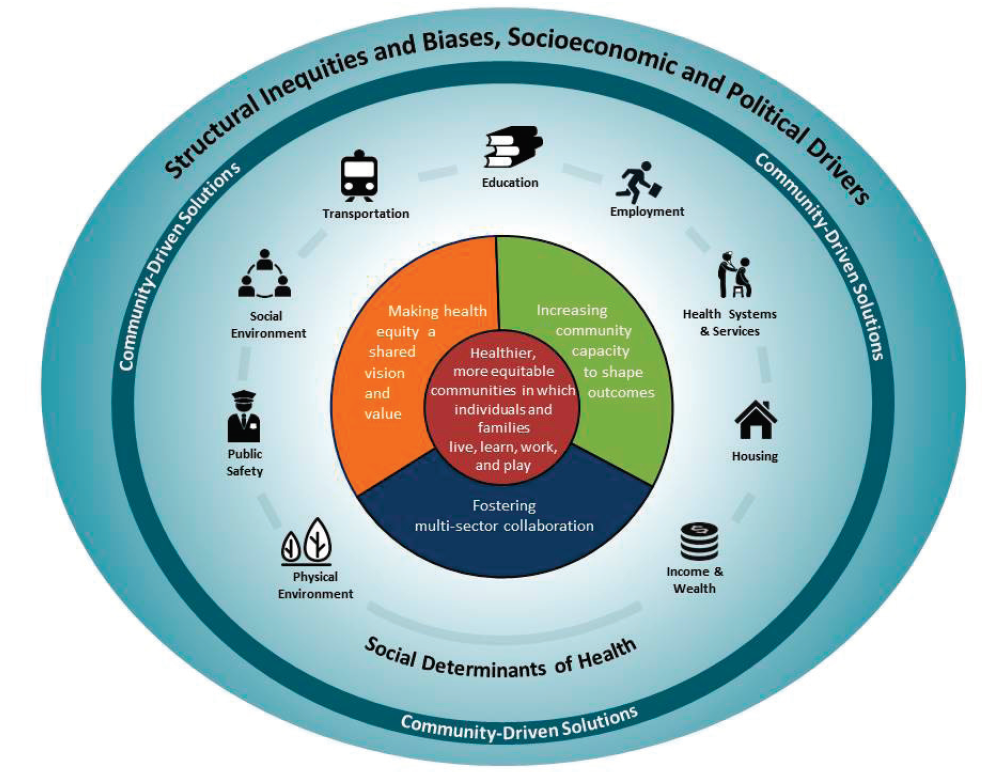

Fig 1. Communities in action: Pathways to health equity. National Academies Press, 2017

The conceptual model titled, Communities in action: Pathways to health equity, and developed by the National Academies can help in working towards community solutions to promote health equity for older adults (Figure 1). First, we need to understand the context in which health inequities exist, which is the outermost circle and background. Structural inequities encompass policy, law, governance, and culture, as well as race, ethnicity, gender or gender identity, class, sexual orientation, and other domains, any of which can refer to actual or assumed characteristics.

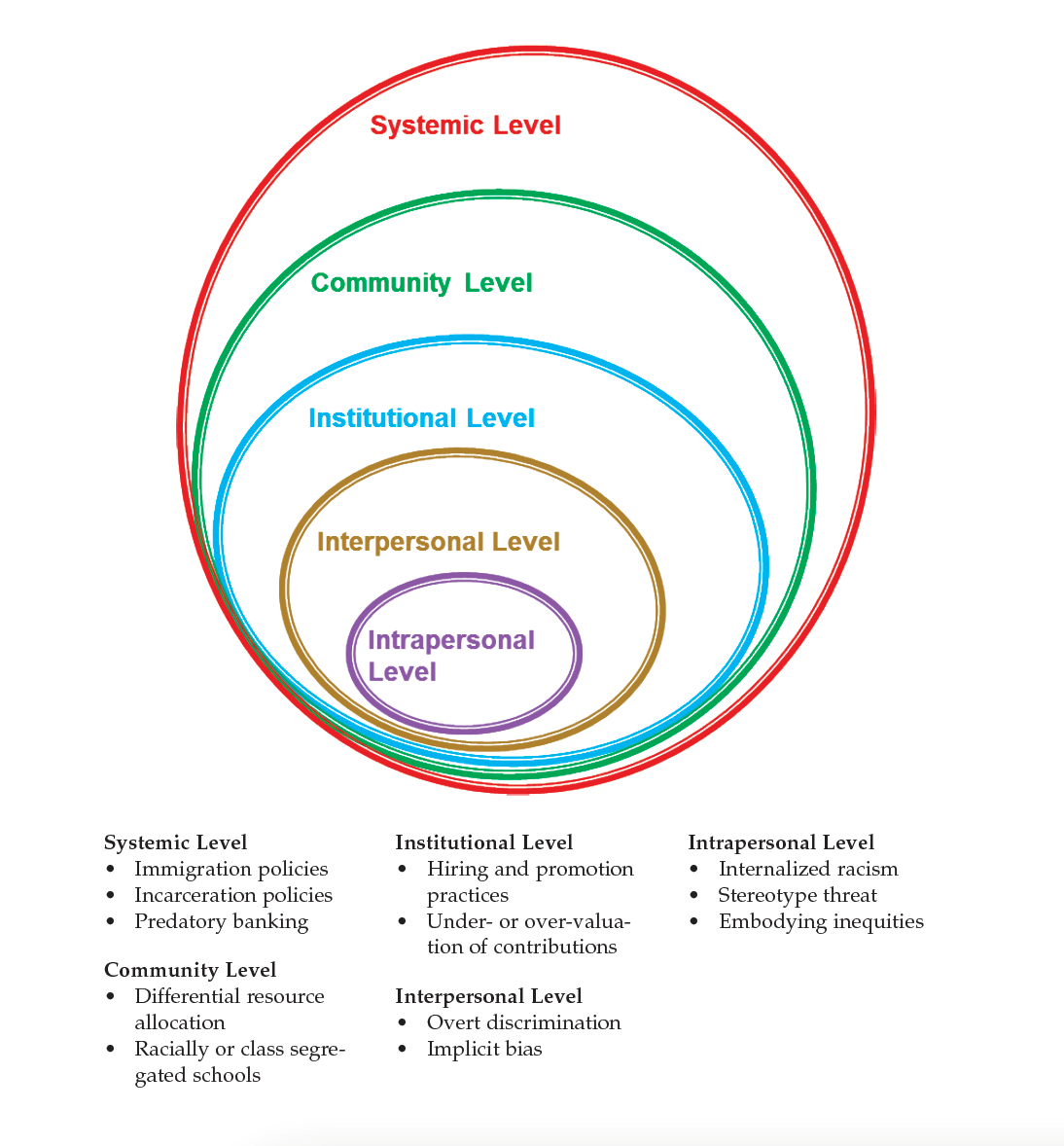

These structural inequities produce systematic disadvantages, which lead to inequitable access to the social determinants of health (e.g., transportation, housing, financial resources, and healthy physical environments) and ultimately shape health outcomes. Structural inequity is an umbrella concept that encompasses specific mechanisms that operate on the intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, community, and systemic levels of a socioecological model (Figure 2).

Fig 2. SOURCE: Concept from McLeroy et al., 1988.

The COVID-19 pandemic has provided a microscopic view of how structural inequities affect the vulnerable older adult population. We must now address the deeper, more entrenched barriers that hamper their equitable access to services and resources, not only in relation to the COVID-19 vaccine, but in many areas that affect their overall health and well-being.

-----

View the entire HIGN November newsletter here

Donation

Donation